Book I, Ch. 5— Grish, Paka, Ica, Adro

Moonthread, by Anthony Lee Phillips

They followed their noses to Grish’s, through the thickening crowd.

Nala had not realized how many beggars there were. Beggar kids. Beggar families. One old beggar stood out, his clothes the filthiest of all. Nala smelled him before she saw him. His wide eyes hugged each item.

He did not look well.

“Someone, give him some water,” Nala wanted to say. Wasn’t there water at each of these stands? And yet, she did nothing. Nala had no water, and didn’t want to lay that burden on someone else.

She was also still a kid, and wished someone else would make the decision to be kind, so she could see how to. If she was more honest with herself, she would have admitted she was afraid of him, too.

The begging man’s eyes lingered on each thing. His fingers nervously, constantly tugged at the frayed hem of his jacket.

He made eye contact with her, which made Nala realize she’d been staring. She quickly averted her gaze.

Grish was working hard. The butcher was a big man, tall with broad shoulders. He wouldn’t have a gut for many years.

The apron Grish wore was made of thick black leather, and tonight, it was splattered with animal blood. He was always scowling, but Grish had kind eyes. His skin was light green, his eyes a bright blue.

There was a huge line at his stand. His grillstone was full, and he was working alone. The smell of good food sold itself.

He took someone’s order, scowling from the stress alone, before turning around to parse apart a long lean loin of beef.

“It’s busy!” shouted Gran.

“Huh?” Grish barked. Then he looked, and said, his scowl melted. “Oh! I was wondering if you’d be by!”

The butcher wiped his sweaty forehead with his shoulder, before chopping three times.

The beggar wandered over. Nala watched him pluck a half-raw flank from the grillstone, slick as an eel.

“Hey!” Grish shouted when he saw the begger. “Hey, get outta here! Thief! Thief!”

He wasn’t wrong, but the quick thief was gone. A part of Nala was happy about it.

“Scum,” grumbled Grish, itching his beard against his shoulder. Then he gave one final chop. “You want some?”

“I’m waiting here!” said the next customer in line.

Grish ignored them, and was already gathering up freshly done flanks before Gran could respond.

“I can’t pay for all this!” said Akha, face drained of all color.

“Pay for what?” grinned Grish, throwing the next batch of meat on the searing hot grillstone.

She tried to hand it back, holding it in the air for him to take.

“Next!” Grish shouted, before turning to his irritated customer. “Alright, what do you want?”

Akha gave a grumpy sigh, but Nala’s delight was naked on her face.

“So good!” Nala shouted, mouth already full.

* * * * / * * * *

They went on.

Nala and Gran passed the three warring weavers, flustered with business at their respective looms. All three occupied the same corner, and they were constantly in competition.

Well, usually; not tonight. Now that they were all three making money, they didn’t seem so cut throat.

I wonder how long that’ll last, Nala thought with a smile.

They sat, and did some people watching. Nala must have gotten that from her Gran, without ever having to learn it, because as they sat there, they looked like clones of each other.

Nala saw a singer lose heart, and a farmer find a lucky bone, lying on the ground. She watched the old mapwitch for a long time, an old Orcish hag named Ica.

Ica had been in the war with Gran Akha, and that’s all Nala really knew about her.

Well… that, and that she was mean as acid.

The old witch had one eye, and both of her tusks were damaged. The left one was cracked, and the other had been seared clean off just above the lip.

Beside the Map Witch’s cart (which she apparently lived out of) was a huge sign that said,

“MAPS, 300 BONES

NO BARGAINING

NO APES

GO BACK WHERE YOU CAME FROM”

Her stand was the only one with no business. The only customers there were a chubby blue-skinned boy and his sister.

The boy was wearing glasses (which was weird) and inspecting a map that was bigger than he was. He was Nala’s age, but much taller, and a little chubby. The boy’s tusks looked more grown up, too.

Nala tongued her tusk.

Patience, I guess.

He was nearly out of earshot for Nala, but her curiosity seemed to give her some (mmm) special ability, so that she could hear every word she wished to.

Nala grinned.

Maybe she was getting her magic after all.

Mmmm…

The witch flinched, and she began to look around.

Mmmm…

Scanning. Nala hid her face, though she couldn’t have said why.

Mmmm…

The old woman couldn’t have been looking for her, so why did Nala feel the need to hide?

“This is incredible!” the boy said, inspecting a map. “Is this…?”

“Put that down,” the hag barked.

“What’s this red ink here?”

The mapwitch snatched it out of his hands, and rolled it back into a scroll.

“Blood,” the old witch said bluntly.

“No it’s not!” He laughed and made a sound, like a snort.

She stared at him, all one-eyed and grim.

“…Is it?” the boy said.

The witch tucked the scroll into an overcrowded bin, smashing some creases into it.

The boy’s sister was more interested in the mapwitch’s trinkets, and had been raking her hands through a tray of cheap rings.

“Don’t touch that!”

“Why not?” whined the sister.

“Why do you think, you little idiot?” snapped the woman.

“Hey!” said the girl. “Don’t call me that! Did you hear that, Paka? She called me an idiot!”

Nala’s heart sank, like a bead of hail in a pond.

“Children,” cursed the witch, as she took a long pull from a bottle.

“You’re not an idiot,” Paka whispered to his sister.

“I know that,” said the girl.

He itched his eye beneath his glasses. That’s when Nala noticed a huge bruise around his eye, turning his dark blue skin almost black.

He picked up another map.

“Wow!” he said.

“Can we go?” whined his sister.

“You gonna buy it or not?” the witch needled.

“Me? No!” the 11-year-old boy said, laughing. “No, I wish! One day, but… Well, I’m something of a mapmaker myself, you see. I—”

“Cartographer,” the hag corrected.

“What?”

“It’s called a cartographer, and… Look, I really don’t care, so if you’re not going to buy it, just… put the map down.”

He did, but continued to look around.

“You ready?” said Gran.

“Huh?” grunted Nala. “Oh— sure.”

She wasn’t really ready to keep walking, but she didn’t want to be disagreeable, so she took a bite and kept listening as long as she could.

“Don’t tear it!” snapped the witch.

The boy sounded hurt. “Why would I tear it?”

“Well you wouldn’t mean to! Unless you were an idiot! Unless you had… What, 300 bones on you? Well, do you?”

“Wh…? …No.”

“Then put it down,” the witch commanded.

He obeyed, though he put it down slowly.

Mmmm…

“I would never have torn it,” Paka grumbled. “I’ve got… clumsy feet, but agile hands, like my father always s—”

“Are you done here?’ the witch snapped.

Nala was mmmmuch too far away now, so it was a mmmmatter of seeing just how far she could go, before (mmm) her hearing went back to normal. The last thing she heard was—

“Can I work for you?” said the boy.

“What?” said the witch.

“What!” said his sister.

Nala laughed, and put a little skip in her step.

“Hey!” Gran Akha said. “You stay close to me!”

“I will,” Nala said, digging into another bite of fatty salted pork.

* * * * / * * * *

Some called it the Springdusk festival, but that was an old name. Everyone knew this night belonged to the grainwitch.

As they reached the Southern district of Market Town, Nala saw the grainwich herself.

She was busy. It was her festival, after all, as it had been for nearly 30 generations now, since the very beginning of this witch’s long line.

“What’s her name again?” Nala asked.

“You don’t know our Grainwitch’s name?” Gran asked, indignant.

Nala blushed and said nothing.

“That’s okay,” Gran said quickly, immediately regretting her wrath. “That’s okay, that makes sense. Her name is Thigu. Thigu Gabnior Botrughee.”

Nala nodded like she understood.

“She’s not going hungry this year!” grinned Gran.

The grainwitch was busy. She was the woman of the hour, and her and her daughters and cousins and aunts did more business than they would ever do again.

This was what they spent the whole year preparing for, and the women were giddy with stress.

The crowd pressed in on them like the hungry mob that it was, as it became clear that there wouldn’t be enough grain to go around ’til the fall harvest came. Even the refugees had enough bones to buy bread, it seemed.

In truth, the grainwitch would walk away with more money than she could figure out how to spend. That summer, food would be far more valuable than money.

But Nala didn’t know that yet. Not really. It was only a whisper of a dream of a feeling, a wisp of air in her belly, a hiss of the goddess that slept in her spine…

Near the very end of Market Town, they came to an area with less shops and more money.

This was the buying crowd.

No more hawkers.

Quieter, too.

The huts here were more elegant, old families, old money. Even out here in the deep Northwestern country, you could tell where all the money went.

First, they passed Adro, the jeweler. He smiled at them, but they didn’t talk. He held out a pillow covered in rings, for a young couple to giggle at.

Adro’s jewelry stand was set up just outside of his front door, with a little green tarp to keep out any rain that might roll through. The tarp was made of cloth, and he put it up every night, whether it was going to rain or not.

Adro was one of the few male mages Nala knew.

It was as rare as witches were common.

Adro was tall and thin, the lankiest orc Nala had ever met. The old man had to hunch just to get in and out of the hut. His goatee was going white beneath his smiling tusks, which he kept in excellent condition.

His long fingers were crowded with rings, sometimes three to a knuckle. They clashed, too, with bands of both silver and gold, emeralds kissing loud rubies, and quiet grey-purple amethysts to match the shade of distant trees. All the colors of his gaudy gems danced in the moonlight.

He had so many rings, but he wore only one necklace. Adro’s pendant was an Orcshire coin, with a hole drilled through the palm so he could feed the string through.

Only it wasn’t an Orcshire coin. In fact, it wasn’t a tribal coin at all. Its face showed a pair of sister moons, one full and one empty. Just like on the curtains in Nala’s house.

She’d never noticed that before.

He infused each piece of jewelry he made with some charm or good feeling. It wasn’t deep magic, not by any means. But once, when she was only 5 or 6, Nala got to try on a tiara he’d made with a gleaming gold topaz.

She remembered it well. When she’d put on the tiara, her whole spine went warm. She spent the rest of that birthnight, grinning like a fool. A giddy fool.

The tiara sat there still, unsold.

But they were far too poor for jewelry, so Gran led Nala deeper into the market.

* * * * / * * * *

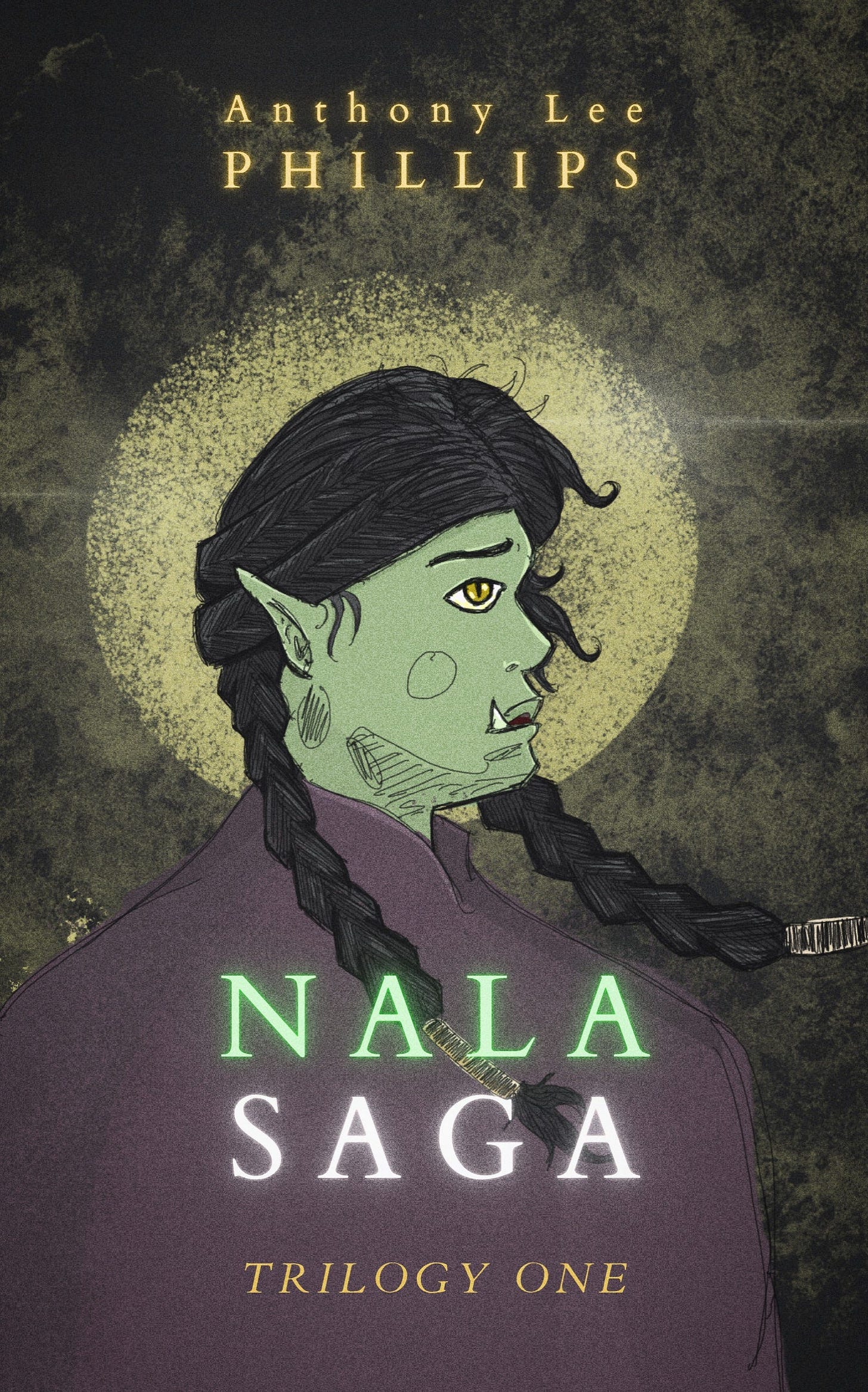

(Art by Jess Tyree.)

GIFT SHOP

Hats & Hoodies

ORC LORE— Poetry about the Gods

* * * * / * * * *

I appreciate how you’re grounding the fantasy world in small, human moments like the the awkward guilt Nala feels seeing the beggar, Grish’s generosity, the way curiosity pulls her toward the mapwitch and Paka. You feel her world expanding with each scene. The moment where her hearing sharpens, that little mmm, is such a clever hint that her magic is waking up. It’s subtle, but it gives you chills if you’re paying attention 🫶💖✨

I really love how you wove the chaotic high energy scenes together. Very artfully done!