There was a signature liquor where Nala grew up, and it was called scrumpy. It was strong, it was strange, and it was very popular. In Orcshire, all the apples were gold, and so was the scrumpy.

As her Gran traded coins for a clay cup of the stuff, Nala smiled.

Not at the smell of it (which made her noise pucker). No, she smiled because they used her family’s apples to make that. In a way, it was theirs, too— or at least, they were part of it.

She was a part of it.

Nala herself had picked some of those apples. All of them maybe.

…Probably not from the cider trees, though. She had neglected that chore on purpose last autumn.

They had three cider trees in her Mama’s applewood orchard, but they were not like the other trees. The apples they dropped were too bitter to eat… at least for most people.

(Not for Nala, but for most people. The people that mattered.)

That trio of trees was tucked away, planted at the very edge of the applewood. She always thought that they looked kind of sad, like they were crying all the time.

It was Nala’s least favorite chore, because not only were they sad to look at, they’d been planted at the foot of Mount Wraithwood, where nothing grew, and nothing died.

The last time she’d been asked to check the scrumpy trees, the moon had been empty. Even on a bright night, all the shadows on Mount Wraithwood got deeper, almost like they were sinking.

On an empty moon night, the shadows between the trees became solid, running upward like tall grooves, or vertical ravines, dividing each leafless, lifeless birch from its neighbor.

Nala shuddered at the memory, forgetting the crowd around her.

That night, she remembered approaching the trees…

…Carefully stepping through a night so dark, even orcs can’t see. The basket was in her hand.

Out of the corner of her eye, she saw some shapeless thing dash through the dense, dead birches. But when she looked, there was nothing to see.

It was then that Nala heard voices.

Animals.

Whimpers.

Whispers.

Howls.

Owls that screeched, and the crying coo of a dying dove.

Yet all she saw was empty mist.

Hello, little ghosts, something said in her.

Nala frowned as she wondered, Does that mean that they died?

The voice in her did not answer, but that was answer enough.

Among the trees, two eyes flashed open, staring straight at Nala.

It had no body that she could see. The eyes seemed to float on the darkness’s skin. Both eyes were bright as full moons, the eyes of a creature not made of mere flesh.

The moment she locked eyes with it, Nala’s head split open with noise. At least, that’s how it felt. She clutched her head with both hands, dropping the basket.

An army of animal ghosts shrieked and wailed and shouted within her, gripping Nala with the kind of terror she only felt in her dreams.

She ran. Ran without thinking, ran with all her might, fast as she could. She got tired, but her fear was strong enough that she wouldn’t let herself top. Her shallow breath was shrill in her own ears, all the way back to her house.

After that, Nala decided to spend her autumn

In the friendlier shadows

Of friendlier trees,

Closer to home,

And less sad.

That was a small part of the orchard, anyway. If there was ever a chore to skip? That was the one. That year, she just tossed in the fruit that came bruised off the branches of sweeter trees.

The boy at the scrumpy stand was not picky about which apples came in the basket.

As Gran took her first sip, it didn’t seem like she minded much either. Nala grinned up at her, and Gran grinned back.

“Onward?” asked Gran, grandly.

“Onward!”

* * * * / * * * *

All the western tribes traded in bones.

Each tribe had its own coin, but they were always made of silver. True silver, too. Nala found herself wondering, Where do you get so much silver?

As a rule, bones were blank on one side, which was called the coin’s heel. On its face, the coin had a symbol. The faces on bones were as different as the tribes that minted them.

Well… “minted.”

Some tribes used a letter as their symbol, easy to replicate and simple enough to do well. Some tribes did even less, scratching sloppy lines on their coins, rough and quick.

Bones like that were crude, but easy to recognize. They wasted no time and got the job done.

The Nur made coins like that. The Yegorah too.

Yegoran bones had only a single mark— an undesigned gash on the silver’s face. Yegorah was a long, long ways away, so not many of those coins made it to Orcshire, but Gran was something of a bones collector.

Orcshire coins were not crude.

Another name for the valley where Nala grew up was the cradle of magic. They did things carefully here. They kept the ways and relayed the stories. That was the way it was when Nala was growing up.

In Orcshire, they still had a coinwitch, and she took pride in their tribe’s symbol— a snake encircling an open palm.

Other tribes might take the easy way and turn to crude tools, like apes, digging into their materials without magic. Not in Orcshire.

“Why are they called bones?” Nala asked.

Gran scoffed out of surprise, and scrumpy came out of her nose.

“Ow!”

“You okay?”

“Yeah,” said Gran, dabbing her nose with her cloak’s sleeve. “Burns though. Say that again?’

“I said, why do they call them bones? They don’t look like bones. I mean, silver is white, I guess, but…”

Gran just shrugged and said, “No one really knows. There are theories, but… Bones are an old idea. Maybe the first Orcs used to trade in real bones? Hard to say.”

“How long ago was the—? Did the, uh…? The first Orcs, how long ago were… they?”

They both laughed together.

“Again,” Gran said, “no one really knows. Old. Very old. Old enough to be legends. Old enough to be myths. Hundreds of thousands of moons ago, maybe.”

“Huh,” Nala said, looking up at the moon.

* * * * / * * * *

As Nala wondered, and Gran sipped on scrumpy, they wandered together, deep into Market Town.

There were musicians, dozens of them. They competed for attention. The singers sung loudly, as loud their lungs would let them, for fear of obscurity. There were ocarina players too (clay flutes, very popular in Orcshire). There were drums (loud) and bells (louder), and even a couple stringed instruments being brutalized for volume.

One blue-skinned kid had a harp.

His pants were caked in the memory of red mud. The boy had a hat in front of him, turned upside down, for donations. It was a floppy hat, made of some pillowy material. A hat made for being seen in, not for staying warm. It was torn, and limp as a rag. Once, it must have been splendid.

Donations were low— just two bones, touching, not even enough for day-old bread.

He was an excellent player, especially for his age (even younger than Nala), but most of his strings on his harp were splayed, broken.

In the din, he played quietly, and they had to get close to hear. The boy’s music was sad— not festival music at all. Maybe that’s why no one listened.

The music had no words. He did not look up as he played. He was lost in the music, and Nala let herself sink into it, too…

…Then, he stopped.

When he stopped, Gran Akha clapped, beaming down at the child. He jolted, looking up, as if he was surprised to find that someone had been listening.

“Beautiful! Transcendent!” Gran said, then she dropped a handful of glittering bones in the hat. The moon lightly kissed the coins, and they glinted yellow as they fell.

The boy smiled so wide it looked like it hurt. His two front teeth were missing, and his tusks hadn’t come in yet.

“Thank you!” he cried, picking up the hate and cradling it with his harp. “Thank you, ma’am, thank you!”

She just laughed. “Eat something!” she told the boy.

“Yes, ma’am!” he said, bowing.

“And when you’re full, share!”

But he was already gone, disappeared, another shape in the crowd, gone before she had a chance to change her mind about how much money she’d parted ways with.

Gran was smiling, and took another sip of golden liquor. She was close to the bottom of the cup now.

“He called me ‘ma’am’ so many times,” grumbled Akha, giggling as she complained.

“Can… we afford that?” Nala dared to say.

Gran shot a look at her, sideways.

“You’re eleven,” she said through squinted eyes. “How ‘bout you let me worry what we can’t and can afford, okay?”

Nala went meek. “Okay.” The wind changed.

“Good. You only get to be a kid once.”

Gran sniffed the air, turning her head toward the smell.

“You smell it too?” Nala said.

Gran smiled down at her. “You still hungry?”

“Always,” grinned Nala.

“How does Grish’s sound?”

Nala’s excitement made her werelight flicker and dance above her head.

Grish’s sounded perfect, smelled even better, and they always got food for free on account of Grish having a crush on Nala’s mama.

“Sounds delicious!”

* * * * / * * * ** * * * / * * * *

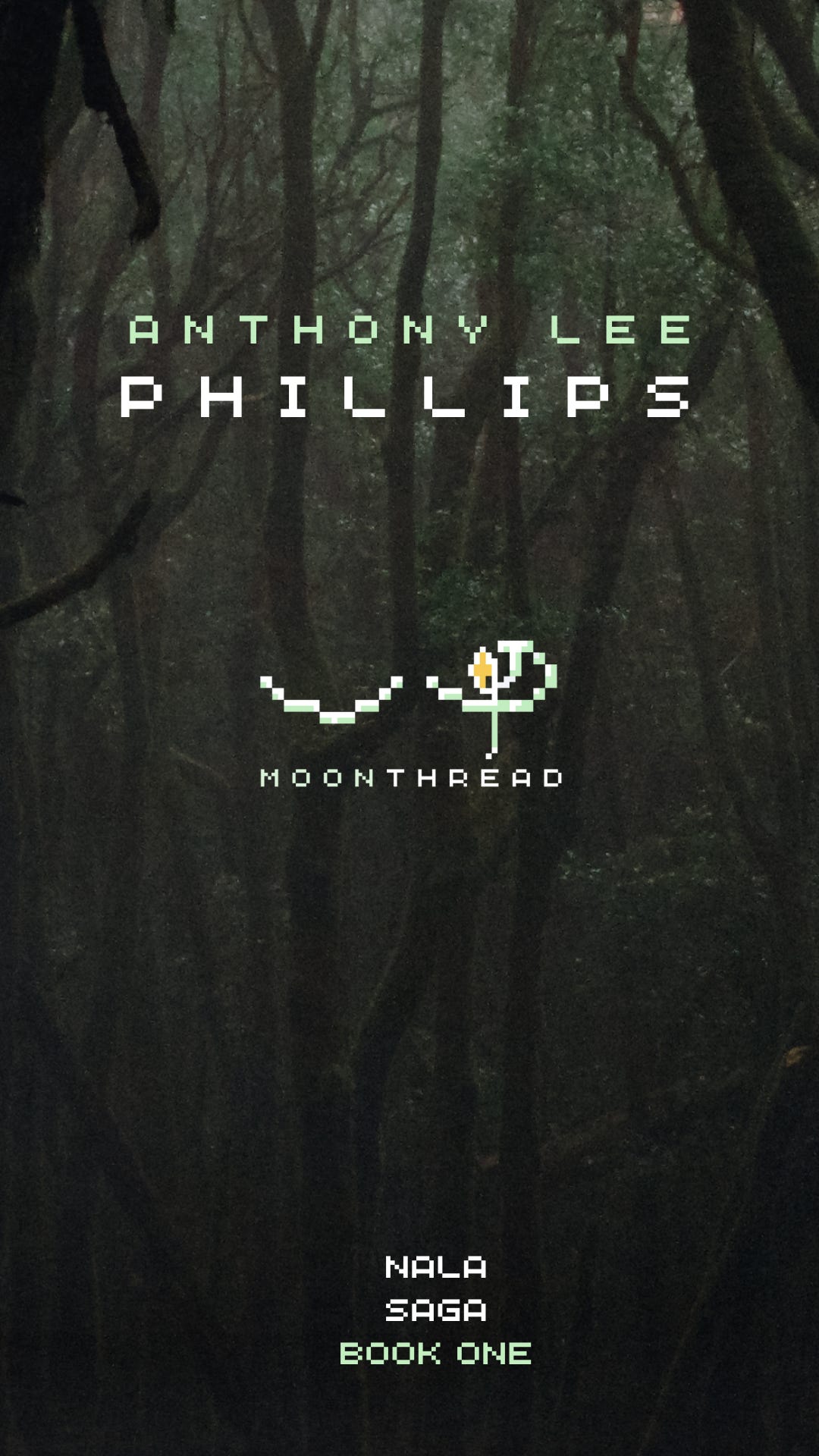

(Art by Jess Tyree.)

GIFT SHOP

Hats & Hoodies

ORC LORE— Poetry about the Gods

* * * * / * * * *

Every time I read it, it gets more thorough and more detailed. I can see the entire scene in my mind's eye. And great addition of alliterations!

This is brilliant. So engrossing! Thank you for writing it.